Open wins in the end. But why?

Closed systems capture value early. Open systems create it forever. From AOL to AI the pattern repeats. Why? - because economic gravity beats corporate strategy.

Back in 1995, the world watched Netscape’s stock price explode on its first day of trading. The internet was suddenly worth billions, and every big company wanted their piece. Microsoft bundled Internet Explorer with Windows to crush Netscape.

Telecom giants pitched their “information superhighway” - basically interactive TV with corporate gatekeepers deciding what you could access. Media companies built walled gardens like AOL and MSN, complete with curated content and premium subscriptions.

They all lost.

Today, we browse with Chrome (built on open-source WebKit), our websites run on the descendants of Linux/Apache/MySQL/PHP stack. Every single dominant web technology came from scrappy open-source projects, not billion-dollar corporate labs. The same pattern played out with mobile networks fighting to capture value in WAP, and now we see the same pattern in the next generation of internet services.

But open systems don’t win because they’re morally superior or because developers love sharing. They win because they make better economic sense.

A tale as old as time

Technology cycles follows the same patterns over time, as while history does not repeat, it does rhyme. And it rhymes because human nature causes people to do the same kinds of things in similar circumstances.

Early market entrants build walls to capture value, people will default to simple ad-hoc adaptations, and as the mental paradigms adapt, networks slowly discover that removing friction creates bigger pools of value than controlling small ones.

Water which is too clear has no fish

Network effects without gatekeepers grow exponentially faster than curated gardens. Innovation at the edges beats innovation in boardrooms. When you remove gatekeepers and licensing fees, networks can grow faster and innovation happens at the edges instead of in boardrooms. More participants means more value for everyone - this is network physics.

We’re watching this same battle play out right now across crypto, AI, and physical infrastructure networks. Companies are desperately trying to maintain control through the usual playbook: proprietary standards, platform lock-in, regulatory capture. But the economic gravity pulling toward openness is stronger than any corporate strategy…

Corporate capture: the pattern repeats

At the birth of the internet there was a plan for the whole internet - “The Information Superhighway”.

Proposed by Cable TV companies the vision was basically interactive television with corporate gatekeepers deciding what you could access. They’d control the pipes, the content, the whole experience. Telecom companies would rent you access to a curated version of the digital future.

But that’s not where we ended up. Flash forward

I worked in mobile during the 2000s, and the carriers were absolutely terrified of becoming a “dumb pipe.” They’d spent billions building 3G networks and thought they’d make it back through premium services. Custom apps and services, WAP portals, carrier billing, approved apps only. Vodafone Live, i-mode, all these walled gardens designed to capture value at the network level.

The iPhone showed up and turned them into exactly what they feared: dumb pipes, utilities for bits and bytes. Now the Apple app store is a great example of a closed system - but it does represent “disintermediation” of quite a bit of market power from the network owner, to a network user. The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.

Now we’re watching the same battle play out with AI, crypto, and physical infrastructure networks. Same playbook: proprietary standards, platform lock-in, regulatory capture.

The corporate capture isn’t just coming from Google and traditional tech giants. It’s also coming from inside the house. Projects that wear the golden robes of decentralization while running a company in the background.

We talk about the “crypto-mullet” - regulated in the front, DeFi in the back. But there is also “the undercut” - DeFi in the front, company in the back. Perhaps you can think of one or two of those.

Progressive decentralization that never quite progresses. Community governance where one foundation holds veto power.

Jesse Walden - Progressive Decentralisation - the ideal scenario

The walled garden of earthly delights

I get why companies build walls. When you’re first into a new market, you have no idea what you’re doing. Nobody does. There’s no playbook for “how to make money on the internet” or “how to monetize AI.” So you do what feels safe: you control everything.

AOL and MSN weren’t being evil when they built their curated gardens. They were solving a real problem. In 1995, the internet was a confusing mess of FTP servers and Usenet groups.

AOL circa 1999

Regular people needed someone to organize it, make it pretty, add some guard rails. “You’ve got mail” in a friendly voice beat the hell out of configuring TCP/IP settings.

The business logic made sense too. You’re burning cash. Investors want to see how you’ll capture value before someone else does. “We’ll be the platform” is a much easier pitch than “We’ll be anonymous infrastructure that anyone can use.” Venture capitalists fund moats, not utilities. They want lock-in, switching costs, network effects they can own.

And here’s the thing: it works. For a while. You move fast because you control the whole stack. You can optimise the user experience end-to-end. No messy standards committees, no waiting for other companies to implement your API. Just ship.

The tiller on the car

When “horseless carriages” were first rolled out, no-one had thought of a steering wheel. Instead most cars had a tiller, like on a boat.

The most available mental model for the horseless carriage… was a steam boat, and so that was the design pattern that was implemented. This is an example of skeuomorphism - carrying over familiar design elements from one technology to another even when they’re not necessarily the most optimal solution.

Early web companies built walled gardens because that’s what made sense coming from publishing and telecom. You use the mental models that exist, even when they’re not quite right for the new medium.

Yahoo organized the internet into categories. Someone at Yahoo decided “Pets” should have subcategories for “Dogs” and “Cats” and you’d click through this directory structure to find what you needed. It seems inefficient now, but in the mid-90s it solved a real problem.

The internet had no structure. No index, no way to evaluate quality, no method for finding anything specific. Yahoo gave you a mental model that already existed: the library card catalog. You knew how that worked.

This is why walled gardens win early. They provide familiar patterns in unfamiliar territory.

The steering wheel came later, once people had time to figure out what actually worked best for cars.

AOL did the same thing. They built channels, chat rooms, a voice that said “Welcome.” It felt like TV or radio, which people trusted. Compare that to configuring TCP/IP settings and understanding DNS servers. For most people in 1995, “something that works immediately” was more valuable than “infinite possibility.”

The cognitive load matters. When everything is new and you’re unsure what’s safe or valuable, curation is a feature not a limitation.

But what starts as helpful curation eventually becomes constraint. Those guardrails that made you feel safe start blocking where you want to go. Yahoo’s categories worked until you needed to search for something that didn’t fit their taxonomy.

Then Google arrived with “search everything” and the old model looked like exactly what it was: a temporary solution.

Today’s Battlefields

The same war is playing out across three fronts right now.

AI is the new OS wars.

OpenAI and Anthropic control access through API gates. You build on their infrastructure, you pay their prices, you live within their rules. Meanwhile Llama and Mistral are out there for anyone to use. Run them locally, fine-tune them for your use case, combine them with other models.

The closed approach works great until developers realise they can get 80% of the capability with none of the lock-in. And now you can coordinate distributed compute networks without a middleman - pay providers directly, verify work cryptographically, route between services automatically. Open models needed open payment rails. Now they have them.

Crypto: internet railroad

Crypto is fighting over the rails. Central banks want CBDCs with programmable controls. Stablecoin issuers want to be the new banking layer. Traditional finance wants to tokenize everything but keep the same intermediaries.

On the other side, you have permissionless protocols where anyone can build, trade, coordinate. Value moves like email now - instantly, globally, without asking a bank for permission. That changes what’s possible.

Physical infrastructure of the internet

AWS and Google rent you compute and storage at margins that would make a feudal lord blush. DePIN (Decentralised Physical Infrastructure) is rebuilding where electrons meet silicon.

Helium, Walrus and Filecoin flip the model: people who run the infrastructure get paid directly by people who use it. No corporate layer extracting rent.

You couldn’t coordinate this before - no way to verify work, route payments, or prevent cheating without someone in charge. Blockchains solved that coordination problem. The network has no owner but it still works.

You cannot change the laws of physics

In every case, incumbents are trying to hold back the water.

You cannot change the laws of physics. Open systems create bigger value pools by eliminating friction, and eventually, that economic gravity pulls everything toward them.

Proprietary APIs that don’t talk to each other. Licensing requirements that exclude competition. Regulatory moats disguised as consumer protection. But closed systems can’t compete with the physics of open ones.

Why Open Systems Win

Network effects

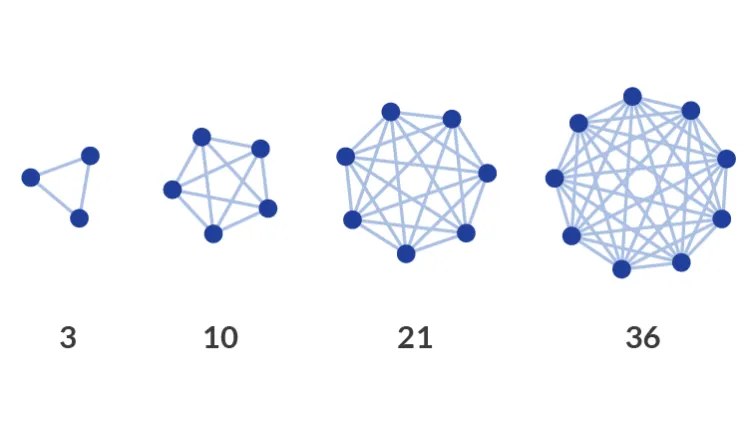

Network effects work better without rent extraction. Every node that joins an open network increases value for everyone else. No gatekeeper taking a cut means faster growth and more participation.

Metcalfe’s law plays out at full strength instead of being throttled by someone’s margin requirements.

Digital commons

As markets mature, people and companies understand where the dimensions of competition are and where it is possible to collaborate with the market. You can look at Open Source Software as shared services, you are sharing development costs with everyone who needs to do the same sort of thing as you, and shared costs with the rest of the market.

Innovation happens faster when it’s distributed. A thousand developers trying different approaches beats a hundred engineers in one building, even if that building has great coffee and standing desks. Open systems get more attempts at solving problems. Most fail, but the ones that work get adopted everywhere immediately.

Antifragility

Open systems get stronger when attacked. Someone finds a vulnerability? The whole community fixes it. A competitor tries to fork and capture value? Users route around them. Closed systems hide problems until they become catastrophic. Open ones solve them in public.

Building an Open Future: a user guide

Minimise friction

Value flows to the lowest friction point. This is just economic gravity - so the focus should be to minimise friction. When you remove licensing fees, approval processes, and platform taxes, you make it easier for people to build and participate. Easier wins.

Composability - plugs and sockets

Design for composability from day one. Your product should play well with others. Make your APIs open, use standard data formats, build integrations that actually work. Think LEGO blocks, not walled gardens.

Leave something on the table

Take a smaller cut of a bigger pie. Sounds idealistic but it’s not. The networks that create the most value attract the most participants. Growing the network matters more than taxing it heavily. You win by being useful infrastructure, not by being a gatekeeper.

Be the pipe

The companies that last become the pipes. Being a “dumb pipe” isn’t losing. Ask Visa. Ask TCP/IP. The infrastructure layer captures less value per transaction but handles orders of magnitude more volume. That’s where the money actually is.

The mobile carriers didn’t want to become dumb pipes. They fought hard against it, spent billions trying to stay relevant as service providers. They lost that fight but won anyway. They’re still here, still valuable, just doing what they’re actually good at: moving data.

Coda

That’s the pattern. Stop fighting physics. Build the infrastructure everyone needs, make it open enough that people want to build on it, and get out of the way.

The value will find you.